Shareholders' Agreement for UK Startups: Key Clauses to Protect Founders

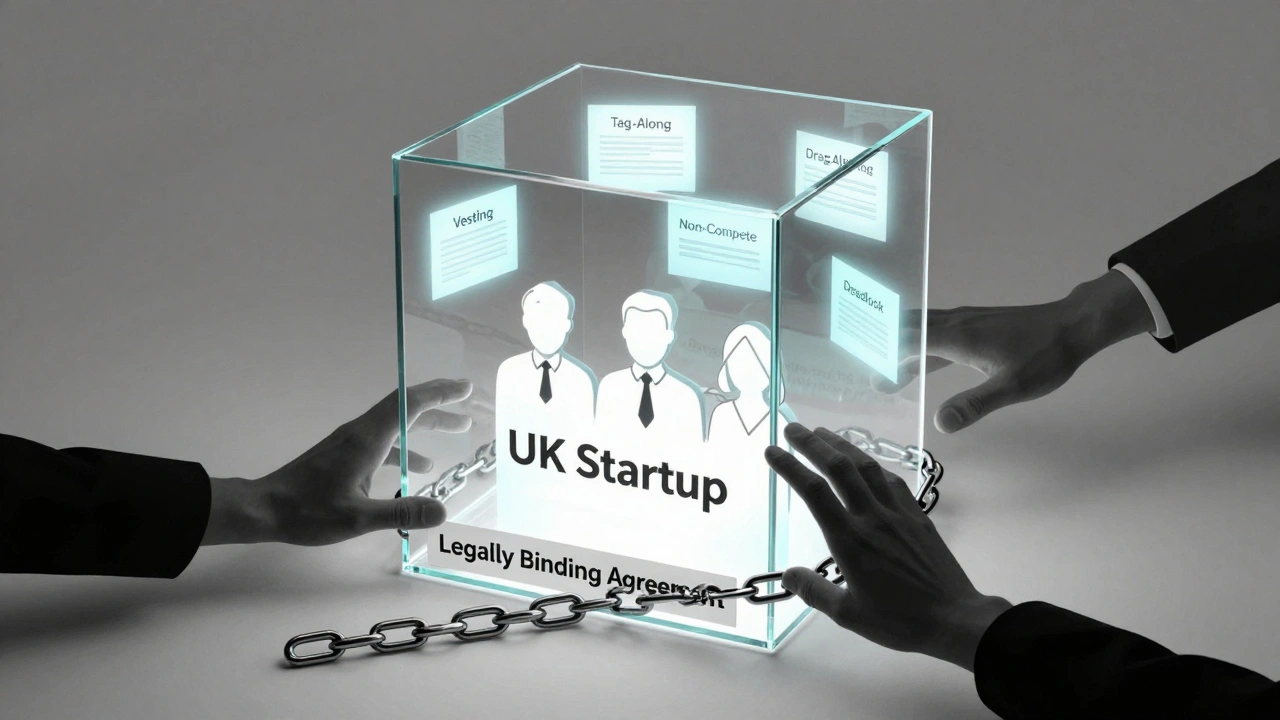

26 Jan, 2026Most UK startups fail before they hit year three. Not because of bad ideas or weak product-market fit-but because founders didn’t protect themselves legally from the very beginning. A shareholders’ agreement isn’t just paperwork. It’s the firewall between your vision and chaos. Without it, one disagreement, a sudden exit, or an investor overreach can wipe out years of work-and your equity-overnight.

Why UK Startups Need a Shareholders’ Agreement

The UK doesn’t require a shareholders’ agreement by law. That’s the trap. Founders assume the Companies House articles of association are enough. They’re not. Articles are public, generic, and designed for standard corporate structures. They don’t cover what happens when a founder quits, gets fired, dies, or clashes with an investor over hiring or strategy.

Real-world example: A London-based SaaS startup raised £500K from a venture firm. Six months later, the investor demanded the CEO be replaced. The articles said nothing about founder control. The investor used their board seat to force the change. The founder lost his stake because he had no agreement restricting removal without cause.

A shareholders’ agreement fixes this. It’s a private contract between shareholders that overrides the articles when needed. It gives founders control, clarity, and protection.

Key Clause 1: Vesting Schedule for Founders

Investors will insist on vesting. Don’t fight it. But make sure it works for you.

Standard vesting: 4 years with a 1-year cliff. That means you earn 25% of your shares after 12 months, then 1/48th each month after. If you leave before the cliff, you get zero. If you leave after, you keep what’s vested.

But here’s the catch: many founders sign vesting without negotiating the trigger. What if you’re pushed out? What if the company fails and you’re forced to quit? You should insist on accelerated vesting on certain events:

- Change of control (e.g., acquisition): 100% vesting if you’re terminated without cause within 12 months after the sale.

- Termination without cause: Full or partial vesting if the board fires you.

Without this, you could work 3 years, build the company, then get replaced-and walk away with 10% of your shares. That’s not fair. That’s not how startups should work.

Key Clause 2: Right of First Refusal and Tag-Along Rights

Imagine one founder wants to sell their shares to a competitor. Or worse, to a private equity firm that plans to gut the company. Without protection, they can walk away with £2 million-and you’re stuck with a stranger as your co-owner.

Right of first refusal (ROFR) fixes this. It says: if a shareholder wants to sell, they must first offer their shares to the other shareholders at the same price and terms. You get the chance to buy them before anyone else.

Tag-along rights are even more powerful. If a majority shareholder sells their stake to a third party, tag-along lets you join the sale. You don’t have to be forced to stay with a new owner who doesn’t share your vision. This stops predatory buyouts.

Example: A founder holds 20% of a startup. Another founder sells 60% to a hedge fund. Tag-along lets the first founder sell their 20% at the same price. Without it, they’re locked in with a hostile buyer.

Key Clause 3: Drag-Along Rights (and How to Limit Them)

Drag-along sounds scary-but it’s necessary. It lets a majority of shareholders force a sale of the entire company, even if some minority shareholders object.

Without drag-along, one stubborn founder could block a £10M exit just because they don’t want to cash out. That kills the company’s chances.

But founders need safeguards:

- Require a supermajority (e.g., 75% or 80%) to trigger drag-along-not just 51%.

- Only allow drag-along after a minimum time (e.g., 5 years) to prevent early pressure.

- Require the buyer to pay the same price per share to everyone. No sweetheart deals for the majority.

Founders should never agree to drag-along with no limits. It turns your company into a takeover target with no say.

Key Clause 4: Dispute Resolution and Deadlock Breakers

Co-founders fight. Even the best teams do. But without a plan, a disagreement over product direction, hiring, or funding can paralyze the company.

Include a clear deadlock clause. Options:

- Mediation first: Both parties hire a neutral mediator within 30 days. If no resolution, move to arbitration.

- Shotgun clause: One founder offers to buy the other’s shares at a set price. The other must either sell at that price or buy the first founder’s shares at the same price. Forces honesty.

- Third-party tiebreaker: Appoint a respected industry figure (e.g., a former CEO or investor) to decide if deadlock lasts over 90 days.

Don’t rely on voting. Equal ownership (50/50) is a recipe for gridlock. Even 60/40 can fail if the minority refuses to cooperate. Structure the agreement so decisions can still move forward.

Key Clause 5: Non-Compete and Confidentiality

If a founder leaves, they shouldn’t join a direct competitor or steal your customers, code, or team.

UK courts are strict on non-competes. They must be:

- Reasonable in time (usually 6-12 months max)

- Reasonable in scope (only direct competitors in the same market)

- Reasonable in geography (e.g., UK only, not global)

Overreach will get thrown out. But a well-drafted clause deters bad behavior. Pair it with confidentiality obligations that last indefinitely-because trade secrets never expire.

Also, include a non-solicitation clause: no poaching employees or clients for 12-18 months after leaving.

Key Clause 6: Transfer Restrictions and Shareholder Approval

Not every shareholder should be able to sell shares to anyone. You don’t want a hedge fund, a stranger, or a rival startup walking in as a co-owner.

Require that any transfer of shares needs approval from a majority of the other shareholders. This gives you control over who joins your table.

Also, specify that shares can’t be transferred to trusts, family members, or shell companies without consent. This prevents backdoor exits.

One founder I worked with tried to transfer 15% of his shares to his brother-in-law to avoid dilution. The agreement blocked it. Saved the company from internal sabotage.

What Happens If You Don’t Have One?

Without a shareholders’ agreement, you’re stuck with:

- The default rules in your articles of association (which are designed for large, stable companies, not fast-moving startups)

- UK company law (Companies Act 2006), which offers little protection to minority shareholders

- No clarity on how to value shares during a sale or exit

- No way to force out a deadweight co-founder

- Legal battles that cost £50K+ in fees and take years

There’s no legal safety net. The moment things go sideways, you’re at the mercy of the other party’s goodwill-or greed.

Common Mistakes Founders Make

Don’t fall into these traps:

- Using a template from the internet: Most are copied from US startups. UK law is different. UK courts interpret clauses differently.

- Signing before legal advice: A £500 template won’t protect you. A £3K lawyer who knows UK startup law will.

- Delaying until funding: Investors will demand one-but you should have it before you take money. Otherwise, you’re negotiating from weakness.

- Ignoring exit terms: If you don’t define how the company can be sold, you’re leaving millions on the table-or worse, trapped.

Final Tip: Review Annually

Your shareholders’ agreement isn’t set in stone. Review it every year. Add new clauses if you bring on new shareholders. Adjust vesting if your team grows. Update dispute resolution if your co-founders’ roles change.

A good agreement evolves with your company. A bad one becomes a liability.

Don’t wait for a crisis to fix it. Write it now. Protect your work. Protect your future. And don’t let someone else decide what happens to the company you built.

Is a shareholders’ agreement legally binding in the UK?

Yes. A properly drafted shareholders’ agreement is a legally binding contract under UK law, as long as it’s signed by all parties, clearly states the terms, and doesn’t conflict with the Companies Act 2006. It overrides the company’s articles of association where there’s a conflict, unless the articles specifically state otherwise.

Do I need a lawyer to draft a shareholders’ agreement?

Yes. While templates exist, UK startup law is nuanced. A lawyer experienced in early-stage tech companies will know how to structure vesting, drag-along, and deadlock clauses to match UK court interpretations. A poorly worded agreement can be unenforceable-or worse, work against you. Spending £2,000-£4,000 upfront saves you £50,000+ in legal battles later.

Can a shareholders’ agreement be changed after it’s signed?

Yes, but only if all shareholders agree in writing. Most agreements include an amendment clause requiring unanimous or supermajority consent. This prevents one party from unilaterally changing terms. Always document changes formally and update the signed copy.

What’s the difference between articles of association and a shareholders’ agreement?

Articles of association are public documents filed with Companies House and govern how the company is run (e.g., voting rights, board meetings). A shareholders’ agreement is private and covers relationships between shareholders-like exit rules, transfer restrictions, and founder protections. The agreement can override the articles, but only if it’s properly drafted.

Can a shareholder be forced out of a UK startup?

Only if the shareholders’ agreement includes a mechanism for it-like a breach clause, bad leaver provision, or shotgun clause. Without it, you can’t force someone out, even if they’re not contributing. UK law protects shareholders’ rights to hold shares unless there’s a clear contractual path to remove them.