Unit Economics for UK Startups: How to Measure Contribution Margin and Payback Time

15 Dec, 2025If you’re running a startup in the UK, you might be raising funds, hiring your first team, or scaling your marketing. But if you don’t know whether each customer actually makes you money-or how long it takes to break even-you’re flying blind. Unit economics isn’t fancy jargon. It’s the bare-bones math that tells you if your business can survive without constant cash injections.

What Unit Economics Really Means for UK Startups

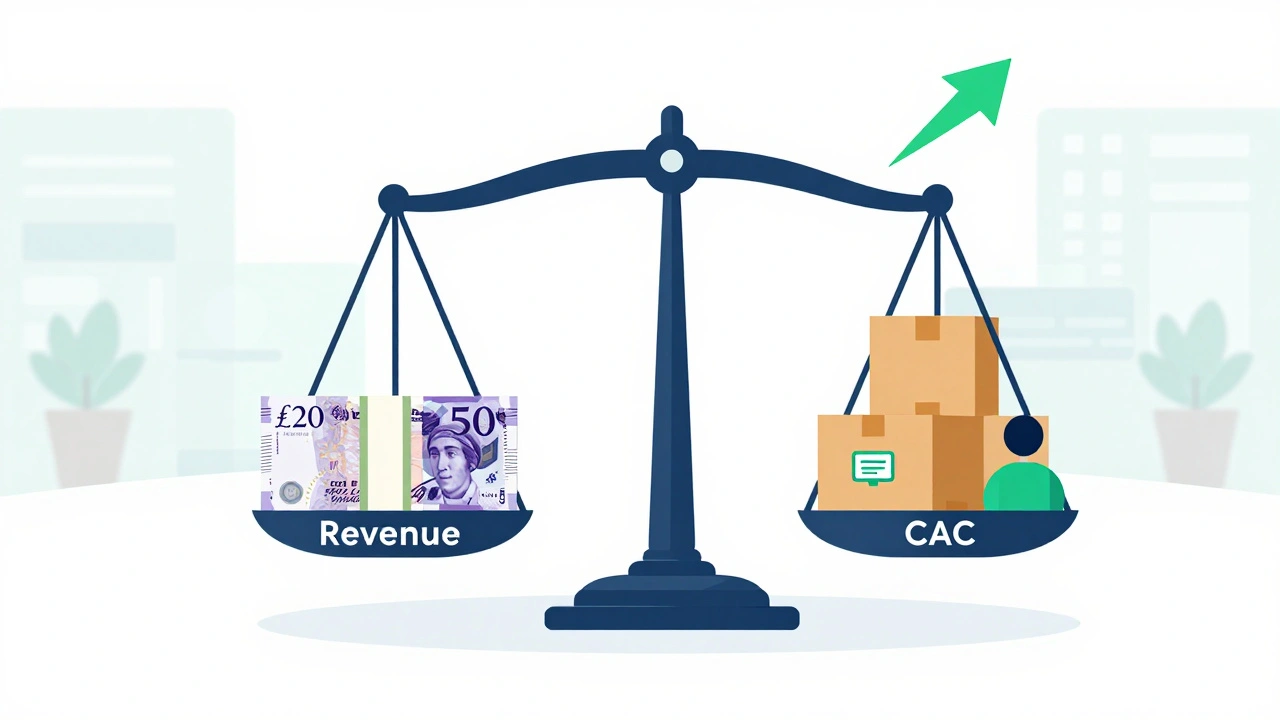

Unit economics breaks down your business into its smallest profitable unit: one customer. It answers two simple questions: how much money does each customer bring in, and how much does it cost to get and serve them? If the answer is ‘more in than out,’ you’re on solid ground. If not, no amount of hype, branding, or investor money will save you.

UK startups face unique pressures: high operating costs, strict employment laws, and a competitive funding environment. Many founders focus on growth metrics-monthly active users, app downloads, social followers-but those numbers mean nothing if the cost to acquire each user eats up their lifetime value. A SaaS startup in London might hit 5,000 users in six months, but if it’s spending £120 to acquire each one and each user only pays £80 a year? That’s a loss of £40 per customer. You’re not growing-you’re burning cash.

Contribution Margin: The Real Profit Per Customer

Contribution margin is the money left over after you pay for the direct costs of serving one customer. It’s not your net profit. It’s not your gross margin. It’s what’s left after you cover the variable costs tied directly to that one sale.

Here’s how to calculate it:

- Take your average revenue per customer (ARPC) over a given period-say, monthly or annually.

- Subtract all variable costs tied to serving that customer: payment processing fees, shipping, customer support hours, platform fees (like Shopify or Stripe), and any third-party services used per transaction.

Example: A UK-based e-commerce brand sells handmade candles for £25. The product costs £8, packaging is £2, shipping via Royal Mail is £3.50, and Stripe takes 2.9% + £0.30. That’s £8 + £2 + £3.50 + (£25 × 0.029) + £0.30 = £14.27 in variable costs. Contribution margin = £25 - £14.27 = £10.73 per candle.

That £10.73 is what you have left to cover fixed costs (rent, salaries, software subscriptions) and make a profit. If your monthly fixed costs are £8,000, you need to sell at least 746 candles just to break even. No more, no less.

Many founders miss this. They look at gross margin (revenue minus cost of goods) and think they’re healthy. But if you’re giving away free shipping, offering live chat support for every order, or paying for expensive ads that don’t scale, your contribution margin collapses. In the UK, where labor and logistics are expensive, this mistake kills more startups than lack of product-market fit.

Payback Period: How Long Until You Get Your Money Back?

Contribution margin tells you if you’re making money per customer. Payback period tells you how fast you get your money back. This is critical when you’re raising seed funding or managing cash flow.

Payback period = Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) ÷ Contribution Margin per Month

Let’s say your CAC is £150. Your customer spends £25 a month and your contribution margin is £10.73 per month. That means you recover your £150 investment in about 14 months (£150 ÷ £10.73). That’s too long.

Most investors expect payback within 6 to 12 months for early-stage UK startups. If yours is 14 months, you’re either spending too much to acquire customers or your product isn’t sticky enough to generate recurring revenue.

Here’s how to fix it:

- Lower CAC: Test cheaper channels-organic social, referral programs, SEO-instead of paid ads.

- Increase contribution margin: Raise prices slightly, bundle products, or reduce variable costs (switch to cheaper packaging, automate support with chatbots).

- Boost retention: A customer who stays 18 months instead of 12 doubles your contribution margin over their lifetime.

A London-based fintech startup reduced its payback period from 15 months to 7 months by switching from Google Ads to LinkedIn outreach targeting small business owners. Their CAC dropped from £180 to £95, and their monthly contribution margin rose to £14 because they upsold a £5/month dashboard feature to 60% of users.

Why UK Startups Fail on Unit Economics (And How to Avoid It)

The most common trap? Assuming that growth equals profitability. Too many UK founders chase venture capital by inflating metrics: ‘We hit 10,000 users!’ But if their CAC is £200 and their LTV is £180, they’re not a startup-they’re a charity.

Another mistake: ignoring indirect variable costs. A food delivery startup in Manchester might track delivery driver wages as a fixed cost. But if drivers are hired per order, that’s variable. If you don’t count it, your contribution margin looks better than it is.

Here’s what to track every week:

- Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) - total sales and marketing spend ÷ new customers

- Revenue per customer - total revenue ÷ number of paying customers

- Variable costs per customer - everything that scales with volume

- Contribution margin - revenue minus variable costs

- Payback period - CAC ÷ monthly contribution margin

Keep these numbers in a simple spreadsheet. Update them weekly. If your payback period creeps past 10 months, pause growth. Fix the model before you hire more people or run more ads.

Real-World Examples from UK Startups That Got It Right

Not all UK startups struggle. Some nailed unit economics early:

- Gousto (meal kit delivery): Reduced ingredient waste by 30% through predictive ordering, cutting variable costs. Payback dropped from 11 to 6 months.

- Monzo (digital bank): Focused on low-cost digital onboarding. CAC under £10 per user. Contribution margin from interchange fees and premium subscriptions. Payback under 3 months.

- Revolut (fintech): Built a freemium model. Free users fund premium ones. Contribution margin on premium users is 8x higher than on free users. Payback on premium sign-ups: under 4 months.

They didn’t win because they had the best app. They won because they knew exactly how much each customer was worth-and how much it cost to earn them.

What Happens When You Ignore Unit Economics?

Picture this: You raise £500,000. You spend £400,000 on ads, hiring, and office space. You acquire 4,000 customers. But your contribution margin is £5 per customer per month. That’s £20,000 in monthly profit. Your fixed costs? £35,000. You’re losing £15,000 a month. Your runway? 3.3 months.

This isn’t hypothetical. In 2024, 43% of UK startups that raised pre-seed funding failed within 18 months-not because of bad ideas, but because their unit economics didn’t add up. The market didn’t turn against them. They turned against themselves by chasing vanity metrics.

There’s no shame in being small. There’s shame in being big and broken.

Next Steps: Build Your Unit Economics Dashboard

Here’s how to start today:

- Identify your top 3 customer segments. Are they B2B buyers? Subscription users? One-time buyers?

- Calculate CAC for each segment. Use actual spend from the last 90 days.

- Track revenue and variable costs per customer. Don’t guess-use your accounting software or CRM.

- Compute contribution margin for each segment.

- Calculate payback period. If it’s over 10 months, stop spending on acquisition until you fix it.

Don’t wait for your accountant to tell you. Don’t wait for your investor to ask. Do it now. Because when the funding dries up-and it will-your unit economics are the only thing that will keep you alive.

What’s the difference between gross margin and contribution margin?

Gross margin subtracts only the cost of goods sold from revenue. Contribution margin subtracts all variable costs-including marketing, shipping, payment fees, and customer support. For startups, contribution margin is the real indicator of profitability per customer.

Is a payback period of 12 months acceptable for UK startups?

It’s the upper limit. Most investors expect payback within 6 to 9 months. A 12-month payback means you’re either spending too much to acquire customers or your product isn’t generating enough recurring revenue. Either way, it’s a red flag for scaling.

Can a startup with negative unit economics survive?

Only temporarily-and only if you’re raising more capital. But relying on funding to cover losses is a strategy, not a business model. Most startups that burn cash to grow never reach profitability. Unit economics isn’t optional-it’s the foundation.

How often should I recalculate unit economics?

Every month. If you’re running promotions, changing pricing, or shifting marketing channels, your numbers will change. Weekly checks are ideal during early growth. Once stable, monthly is enough.

Do I need software to track unit economics?

No. A simple spreadsheet with your revenue, CAC, and variable costs works fine. Tools like QuickBooks or Xero can automate it, but you don’t need them to start. The key is consistency-not complexity.